I recently finished reading the Charles Dickens’s classic, A Tale of Two Cities, a story of sacrifice and revenge before and during revolutionary France. Dickens was partially inspired to write the novel to to develop some of the themes he had addressed in previous novels, namely poverty. He insisted that if things did not change, violent revolution in England, similar to the French Revolution, was possible. He was wrong then, but the French Revolution is not a lesson easily ignored in our age, where men and women are forced to beg for work, and enslave themselves to keep it.

Looking back on classic literature like Dickens, I’m stunned at the relevancy of it all. The introduction begins with one of the most recognizable openings in all of English literature.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way— in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

The contrast between two sets of characteristics shows a society crumbling at the foundations, while illusions and arrogance are common elsewhere among the elite class. Here, Dickens states that pre-revolutionary France 80 or 90 years prior was not so different than England in his time. The people were suffering; the politicians, out of touch and believing they were secure, were content to wallow in the excesses of profound luxury. As Dickens says, it was “like the present period.”

In the novel, the bloodthirsty tavern owner and French citizen Ernest Defarge and his wife Madame Defarge, see the violent overthrow of the monarchy coming years before it happened. They work at great length throughout the first two thirds of the novel to prepare and maximize its effectiveness when the people finally do rise up.

Rather than voicing their outrage and complaining about the lack of justice and the poor conditions they are forced to endure, the Defarges try to keep the elite establishment oblivious and complacent. They encourage the children to yell praises at the aristocrats and royalty as they pass. Defarge says:

“Make these fools believe that it will last for ever. Then, they are the more insolent, and it is the nearer ended… Let it deceive them, then, a little longer; it cannot deceive them too much.”

Defrange and his wife want to keep the establishment out of touch, complacent and illusioned, so to cause the impending revolution to happen all the sooner and to keep the establishment from taking preventive measures — measures which might make the lives of the peasantry more bearable. Like most real life revolutionaries, they are accellerationists and absolutist; they don’t seek piecemeal reform that might modestly improve their lives, rather they want total victory and the revenge that comes with it.

Through Madame Defarge, Dickens warns readers that the tides of revolution can come without warning.

“It does not take a long time for an earthquake to swallow a town. When it is ready, it takes place, and grinds to pieces everything before it. In the meantime, it is always preparing, though it is not seen or heard. Although it is a long time on the road, it is on the road and coming. It never retreats, and never stops. It is always advancing. Look around and consider the lives of all the world that we know, consider the faces of all the world that we know, consider the rage and discontent to which the Jacquerie addresses itself with more and more of certainty every hour. Can such things last?”

When the Revolution begins and blood is spilled throughout France, Dickens characters note that their revenge is not free. Murder, justified or not, takes a personal toll on their humanity, even as it becomes easier and easier with the multitude of victims. A violent society quickly destroys not only itself, but its culture, and its sense of basic decency. Dickens writes:

“The raggedest nightcap, awry on the wretchedest head, had this crooked significance in it: ‘I know how hard it has grown for me, the wearer of this, to support life in myself; but do you know how easy it has grown for me, the wearer of this, to destroy life in you?'”

If there is a lesson to be learned from the French Revolution, it is, as Albert Camus once wrote, that “Doves do not perch on gallows.” Violence begets violence. It takes its toll on the humanity of its participants as they become increasingly comfortable with killing. It’s always self destructive. Put another way, if you live by the sword, you will die by the sword.

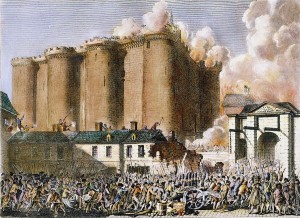

The French Revolution is often cited as the beginning of the “modern era,” an age that was birthed through widespread suffering, hyperinflation, populist ideals and eventually, extreme violence. By modern era, historians usually mean liberal, secular governments that derive their authority from the people, and therein lies the problem we face today.

As William Faulkner once wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” In most respects, many of the positive trends initiated by the French Revolution have been reversed. The aristocrats of today are little wiser than King Louis the XVI. At present, nearly 50 million Americans, roughly one in 6.5, are now on Food Stamps. Unemployment as a percentage of population hasn’t budged in five years. And the list of grievances grows with every secret bailout.

As William Faulkner once wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” In most respects, many of the positive trends initiated by the French Revolution have been reversed. The aristocrats of today are little wiser than King Louis the XVI. At present, nearly 50 million Americans, roughly one in 6.5, are now on Food Stamps. Unemployment as a percentage of population hasn’t budged in five years. And the list of grievances grows with every secret bailout.

The political situation is even worse. No self-respecting social or political analyst would claim the United States is still a liberal democratic republic. If we ever had free governments, they have long since reverted to a pre-revolutionary state where the power elite control all wealth (directly or indirectly through corrupt laws), rights are given and taken away based on convenience and the authority to govern is derived from force of arms, not from the will of the people.