George Carlin once joked that mankind has done little more than demolish, harvest, strip-mine and otherwise blast nature into the past, where men of science hope it will stay, out of sight and out of mind, a phantom of a world that no longer exist except in very specific fenced in areas for tourist to gawk before returning to the straight lines and certainty of civilization. Science, like Satan himself who proudly defied God to give man knowledge, is in essence a continuation of that biblical rebellion; our search for knowledge we believe will lead to new powers, ultimately even the power to defy death, or so we tell ourselves.

The truth is that despite our best efforts, nature cannot be conquered, destroyed or even effectively managed; even with a total understanding of it’s function, the laws of the universe have a way of snapping back, smacking us right in the face. The designs of nature are long term, cyclical, and omnipresent while the machinations of science are short term, short sighted and exploitative. This gives the machine world a short term advantage because machines do not give back, but ultimately ‘resource extraction’ is devoid of meaning and eventually devoid of the resources it needs to continue. Collapse is the result. Nature snaps back.

Nature is different in that it uses death as a core component of its rejuvenation. Life springs from death. In fact, you cannot have new life without death. This dynamic plays itself out repeatedly throughout the universe. If you want to plant a tree, you don’t plant it in a pile of seeds, but in the dirt, which really is everything that has died before.

Many scientists hope that we will be able to finally defeat death, either by transferring our consciousness to machines or developing methods to keep our bodies cells from decaying, but nature tells us this that while we may master the individual components of life, life as we know it requires death. Life, without death, is a hollow shell, like our concrete buildings and corporate offices which function to serve our desires yet utterly fail to serve our much broader communal needs.

When nature does snap back, it can be a beautiful thing. Instinctively, we seem to recognize this, almost pleading for some kind of apocalyptic movement that will provide the possibility of new life — a death-nail to our old culture so that a new one can take its place, vibrant and alive. The underlying principle would seem to be, “Give me liberty or give me death.” Alas, it seems that what we really need and perhaps on some level want, is both.

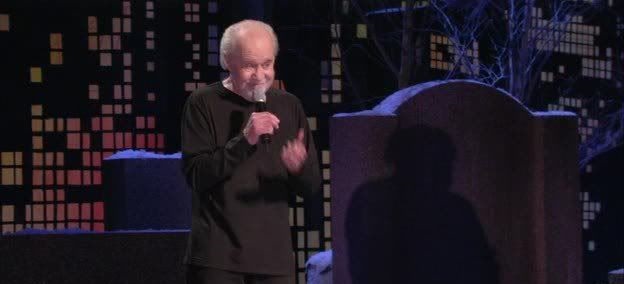

Comedian George Carlin seemed to agree. In one of his final HBO specials, Life IS Worth Losing, Carlin explained that in a sense, destruction was a joy for him. He said:

I have absolutely no sympathy for human beings whatsoever. None. And no matter what kind of problem humans are facing, whether it’s natural or man-made, I always hope it gets worse.

Don’t you? Don’t you have a part of you that secretly hopes everything gets worse? When you see a big fire on TV, don’t you hope it spreads? Don’t you hope it gets completely out of control and burns down six counties? You don’t root for the firemen do you? I mean I don’t want them to get hurt or nothing, but I don’t want them to put out my fire. That’s my fire – that’s nature showing off and having fun. I like fires.

He continues on like this for some time, but you get the idea. Disaster when it concerns mankind’s creations is undoubtedly fun. Certainly film audiences from the 1970s would agree. Consider 1974’s The Towering Inferno, starring Steve McQueen and Paul Newman, where man’s arrogance, or perhaps just plain old naivety, turns a skyscraper into a pile of smoking rubble. The 135-story building symbolizes, to quote the movie directly, “a kind of shrine to all the bullshit in the world.” There was apparently a sense even then that there was something not quite right about what we have done.

Freud seemed to agree, arguing in Civilization and its Discontents that humans had a “death instinct,” meaning there was always an unconscious desire to return to an inorganic state and this could be visibly observed in man’s outward aggressiveness. This aggressiveness, he concluded, was “the greatest impediment to civilization” one that a cultural superego or cultural-conscience could limit. Essentially, we are told to suppress these urges to tear down the walls and machines, to look down upon our obvious love of their destruction because, we tell ourselves, these machines and concrete structures have value.

Freud seemed to agree, arguing in Civilization and its Discontents that humans had a “death instinct,” meaning there was always an unconscious desire to return to an inorganic state and this could be visibly observed in man’s outward aggressiveness. This aggressiveness, he concluded, was “the greatest impediment to civilization” one that a cultural superego or cultural-conscience could limit. Essentially, we are told to suppress these urges to tear down the walls and machines, to look down upon our obvious love of their destruction because, we tell ourselves, these machines and concrete structures have value.

The type of thinking that hopes for fires and scarcity and turmoil and violence flies in the face of everything we’ve been told about what we say we want: good jobs, a nice house, and of course, money. With the destruction of the current paradigm, there is a new hope for a spiritual restoration, one that even overwhelms our fear of the unknown. We think it’s sick and yet somehow, we know it’s entirely understandable and desirable. As the bulwarks of our cultural-conscience crumbles, the death instinct–our desire for rebirth, becomes more and more prominent.